|

<< Previous

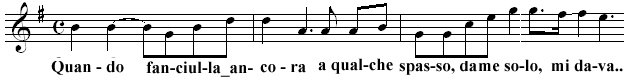

In connection with Mascagni's use of the broad melody, one particular trait of his should be observed. It is the practivce of presenting a theme first by the voice, and then later, on its return, transferring it to the orchestra (often in another key) while the voice weaves around it using the accompanying harmonies as its raison d'être and the declamation of the text as its rhythmic basis. A perfect example of this may be found at the beginning of this same second act narrative. Ratcliff begins his speech with this wonderful tune:

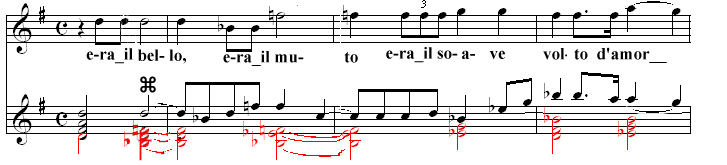

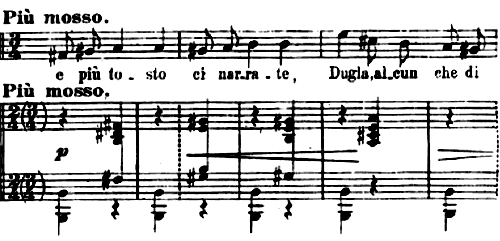

Thirty-five bars later it is presented in this manner:

Note that the orchestra now plays in B-flat, with the theme beginning on the third beat of the bar (in black, at the symbol  ) rather than the first, and how the vocal line, by following the cadence of the text, seems to be in another rhythm. ) rather than the first, and how the vocal line, by following the cadence of the text, seems to be in another rhythm.

One thing about the preceding example will strike the attentive listener, even on first hearing: the exremely high tessitura for the tenor voice. this love of the bright sound of the tenor's top register was never to leave Mascagni throughout his entire career and has been the despair of more than one tenor. From a practical point of view it can also be seen as one reason for the neglect of Mascagni's operas. The part of Ratcliff is written for a heldentenor (the first singer of the rôle was DeNegri, famous for his Wagner interpretations in Italy) coupled with an Italian lyricism which demands both warmth and brilliance.

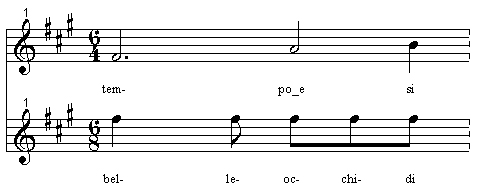

The penchant for deliberately complicating simple things is evident on many pages of Mascagni's early music. Eventually his style became more straightforward, but even in Cavalleria Rusticana we can see his almost naïve insistence on layering a 6/4 meter in the men's chorus with a 6/8 meter in the women's:

...then subdividing a 3/4 measure into a 4/4 measure, as though the bottom quarters are eighth note triplets...

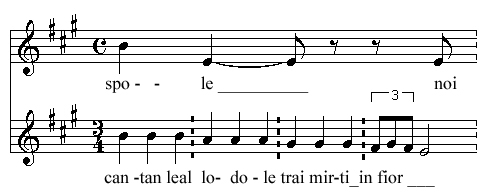

...and finally alienating all three sections at one point, with all three meters going at once. The listener isn't likely aware of this battle of the meters (even those who know the score well don't seem to realize what's going on), and it's all much, much too complicated for the final effect. (Purists will disagree.) In Ratcliff there is a remnant of this tendency in the first scene, where poor Maria is singing along in 3/4, and the accompaniment suddenly breaks off into 2/4, with the pulse the same quarter note in both sections:

All this means is that there are 6 measures for Maria in 3/4 time, while the orchestra plays 9 2/4 measures in the same space of time. The only effect is that the downbeats appear in odd places (as Mascagni meant for them to be). But it's a cautious and somewhat disingenuous method that is an example of the kinds of experimentation he was lavishing on this opera, his love-child.

|