|

<< Previous

4. The Score of Guglielmo Ratcliff

Any serious study of Mascagni's music must perforce begin with Ratcliff, his first important work. Indeed, for the true mascagnano it forms the first pillar of a great triple edifice, the others being Iris and Parisina. every compositional device, every harmonic turn, every melodic thumbprint that was later to be refined and amplified into the stupendous fresco that is Parisina is prefigured in this "first" opera of Mascagni. This is not the place for a full musical analysis of Ratcliff, but a survey of the manin outlines of its musical fabric may help the new listener find his bearings as he approaches this vast labyrinth for the first time.

As has been seen from the preceding seies of letters and autobiographical material, Mascagni worked inermittently on the first version of the opera from 1882, when he first discovered the translation, until 1889, when it was regretfully laid aside to enter the Sonzogno contest with Cavalleria Rusticana. In 1893-94, when he returned to it again for final revision, he had the experience of three performed operas under his belt (i.e: Cavalleria Rusticana, L'Amico Fritz, and I Rantzau) and, though the original version is no longer extant, we can be sure that he subjected his already composed material to the most severe scrutiny. In a letter to Vichi not included in the above section he stated that he had set every syllable of Maffei's translation, but proof of his severe editing is seen by the fact that when he came to publish the libretto of Guglielmo Ratcliff he indicated with underlinings those sections which were not set to music. Already the practical musician of the theatre is at work. But the youthful exuberance that glows in every bar of Ratcliff has been left intact and one can only be grateful that Mascagni's "providence for musicians" saw to it that Ratcliff was not his first opera.

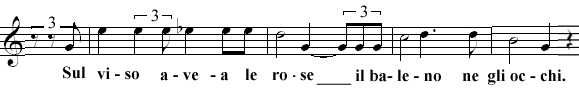

Mascagni was devoted throughout his entire career to the exact setting of the musical capacity of his texts. this is in great evidence already in Ratcliff, although not to the extent we will find in the later scores, particularly Lodoletta, and of course Parisina. Even when he writes a great long-limbed melody, it is the word that will govern its future use in the opera, if any. For example, in Guglielmo's great Narrative in Act Two, the following sensuous theme occurs, when he describes to Lesley his first meeeting with Maria:

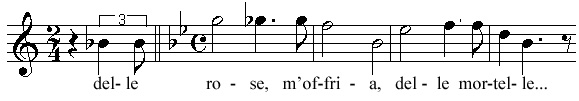

Note the triplet on the second beat as opposed to the duplet on the fourth in the first bar; the first syllable of the verb "avea" is not nearly so important as the article "le" for its noun "rose"; it is almost as if the composer wished to draw attention to the word "rose". His reason for this emphasis becomes apparent when the melody is brought back a second time:

A small point, perhaps, but one that gives an insight into the working of this fastidious (the word is not used lightly) composer.

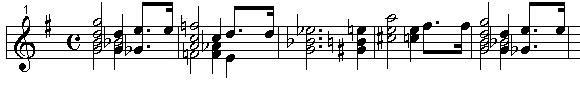

While Stivender is speaking of the precision with which the text is placed, it should be pointed out that the musical language itself is one that is still strikingly original today. The opening notes of Ratcliff are at once noble, decayed, gloomy, and coruscating.

This major-minor-major sequence has a built-in swirling centerless to it that seems to define the unreality of this tragedy, based soley on feeling rather than logic or even common sense. The keys seem to slip from one to the other in a madness that Bach would have found amusing: G-major/G-minor, passing to F-major/F-minor, passing again to E-flat, then E leading us to A-major, falling to A-minor, back to the opening G-major/G-minor sequence. The sequence brings us to B-major, and then enharmonically back to G (i.e: the note "B" is common to both keys). Enharmonic relationships are very important to Mascagni's music, and were the despair of Verdi who complained of the young composer's reliance on "false relations."

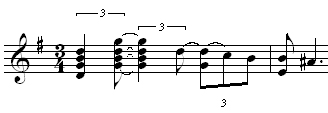

What we don't realize on first listening is that this prelude is the whole fourth act in miniature; we will hear nearly the entire prelude again at that time, illustrated with the lyrics; this is a prefiguring of the opera's last few minutes. The main theme of the prelude, which is a powerful romantic theme, is curious in itself, as it is exemplary of one of Mascagni's most distinctive traits. He enjoys offsetting the melody in its natural stresses for a distinct purpose. The melody "should" be something like this, foursquare and simple:

But nothing is ever that simple to Mascagni. He forces this tune into a sort of 'measured rubato' - with the melody staggered among tied triplets on their off-beats, and the melody itself coming to a pause not on the note A, but A-sharp, giving it a very unsettled quality. If ever there was a musical representation of a maverick, this is one—both Ratcliff and Mascagni.

However, despite the unsettledness of the theme, its constant beat-displacement is advantageous because one can hear the very foursquare, plodding accompaniment better, as though the top voice were glimpsed through the latticework of the musical ground.

|