|

<< Previous

In addition to his concern over the individual words of the text is his delight in small realistic touches in the orchestra, which describe whatever action is being narrated. This was almost a stock-in-trade of the Italian composers of the period (the mantle of Wagner hung heavily on them), but only Mascagni and Puccini were able to manage these small touches so delightfully. Think, for example, of the delivious moment in the first act of La Bohème where Rodolfo sprinkles water on the fainting Mimì (pizzicato strings and harp), or the clink of the coin on the table at Minnie's words "aspettando cader qualche moneta" in the first act of Il Fanciulla Del West. Ratcliff has its share of this sort of thing, too, the most amusing of which is probably the moment at the end of Act Two when Taddie tells John that their friend Rissel is to be hanged that morning. The orchestra kicks its heels in the air:

Also to be noted are the wonderful touches in Ratcliff's second act narrative at the words "Il canto degli augelli" where in succession are heard the birds' song, their amorous greeting, the mumur of the fountain, and the zephyr lightly blowing.

While it is most disingenuous for me to differ with Maestro Stivender on such subjective observations, these particular touches of musique concrète in this opera seem to me to be the weakest part of it. The one-to-one correspondence of music to action was discredited in the movie industry as "mickey-mousing," that is, trying to consciously imitate in music what was already there visually on the screen. The allusions to the fischio of the wind, in libretto and atmospheric orchestration, particularly in the opening of Act Three is the other obvious example.

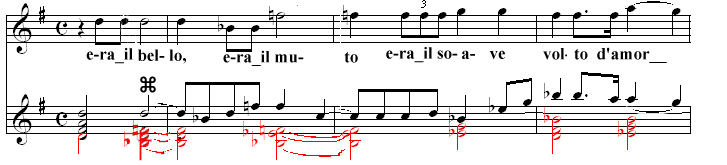

In its open fourths in the flutes and a tremolando in the basses, it is a musical perception of wind that I think sounds more like an Italian tramontana than a blustery Scottish wind over a moor! In any case there are musical elements more emblematic than these in Ratcliff. In the aforementioned example, where the orchestra plays in B-flat and the tenor sings above it:

...there is a further development in that just as this example ends the tenor and the orchestra are singing in unison, and continue to do so for a few more measures. When the theme finally reappears at the end of the narrative, this same gesture happens again; the orchestra and tenor are separated by several beats, but again find each other and then sing to the climactic moment of the number in unison. It is a very powerful effect, saying subliminally (certainly not explicitly) that Ratcliff has finally reconciled his wild fantasies and has brought it all together into a stream of action.

|